Hooded grebe

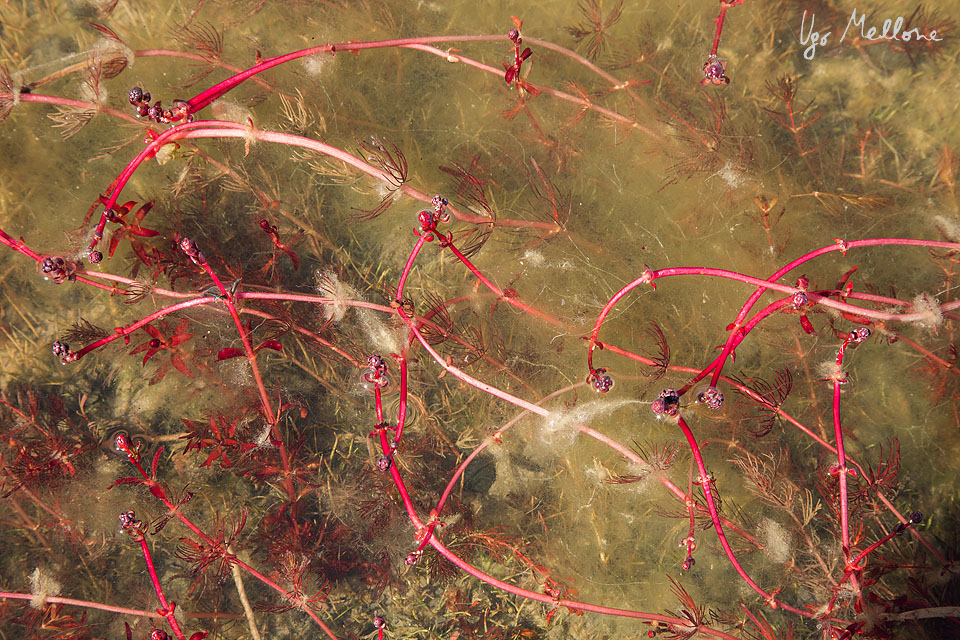

A breeding lake in the Buenos Aires lake plateau, inside the recently established Patagonia National Park. At the beginning of the reproduction season, the milfoil does not yet reach the water surface.

The milfoil (Myriophyllum quitense) provides to the grebes the best support for building their nests, as well as the habitat for their invertebrate preys.

In order to study and protect the grebes, “colony guardians” camp for several months beside the lakes. They check daily the development of the colonies and prevent attacks from predators. According to the latest data, around 800 mature individuals are remaining, while in the 80’s the estimation was between 3000 and 5000.

Hooded grebes and Chilean mountains on the background.

In order to establish the pair bond, hooded grebes perform a complex display, involving several different postures. Is not easy to witness the complete display, because often it is interrupted by other individuals.

In order to establish the pair bond, hooded grebes perform a complex display, involving several different postures. Is not easy to witness the complete display, because often it is interrupted by other individuals.

The courtship continues with exchanges of milfoil, used to build mating platforms and nests.

Hooded grebes mating.

Competition for mating platforms may be fierce, and fighting are frequent: here, with the sympatric silvery grebe (Podiceps occipitalis).

Patagonian winds are strong and constant: even if colonies are located in the most sheltered areas of the lakes, incubation, which lasts 21 days, is a very critic stage of the life cycle. Extreme weather events associated with climate change are becoming cause of concern for the future of the species.

Whenever possible, wardens collect abandoned eggs in the attempt to raise in captivity a second juvenile. Within such a dramatic scenario, every individual counts.

New born grebes spend the first three-four weeks of their lives on the back of the parents, which feed them with aquatic invertebrates.

Tens of traps are placed every year in all the rivers that may lead to the breeding lakes, in order to kill American minks (Neovison vison). This alien species may destroy a colony in just one night.

The decrease of snowfalls in the last years is making waterless many former breeding lakes.

As in other grebe species, also hooded grebes ingest feathers to facilitate digestion.

Known to science only as of 1974, the hooded grebe (Podiceps gallardoi) is now critically endangered. Less than 400 pairs still breed in remote lakes scattered across the high volcanic plateaus of Patagonia, in Southern Argentina. This species represents a paradigm of the ongoing mass extinction crisis in that, even remote areas, supposedly risk free of man-induced threats, are losing their biodiversity. The main triggers of such a decline are attributed to the introduction of alien species and climate change.

A group of researchers and conservationists belonging to the NGO Aves Argentinas (Birdlife International) is striving to halt the hooded grebe decrease. They control the whole breeding cycle of the species, working under harsh conditions, but rewarded by the observation of the amazing courtship displays. The establishment of the new Patagonia National Park is one of their first conservation achievements. However, their efforts may be undermined by the construction of a dam on Rio Santa Cruz, that will irreparably damage the wintering grounds of the species.

Descritto dalla scienza solo nel 1974, il macá tobiano (Podiceps gallardoi), noto in Italia come svasso dal cappuccio, è ora una specie molto minacciata. Meno di 400 coppie si riproducono ancora in remoti laghi situati sugli altipiani vulcanici della Patagonia, nel Sud dell’Argentina. Questa specie è un paradigma dell’estinzione di massa attualmente in corso: anche le zone piú remote, che si supponeva fossero libere dalle minacce causate dall’uomo, stanno perdendo la loro biodiversità. Le principali minacce per la specie sono le specie alloctone e i cambiamenti climatici.

Un gruppo di ricercatori e conservazionisti appartenenti alla ONG Aves Argentinas (Birdlife International) sta lottando per fermare questo declino. Svolgono un costante monitoraggio delle colonie, lavorando in condizioni molto dure, ma ricompensati dall’osservazione delle spettacolari danze di corteggimento. L’istituzione del Parco Nazionale della Patagonia è uno dei loro primi risultati. Tuttavia gli sforzi potrebbero venire compromessi dalla costruzione di una diga sul Rio Santa Cruz, che pregiudicherebbe in maniera irreparabile la principale zona di svernamento degli svassi.

Descubierto por la ciencia solo en el 1974, el macá tobiano (Podiceps gallardoi), es ahora muy amenazado. Menos de 400 parejas se reproducen todavía en remotas lagunas localizadas en los altiplanos volcánico de Patagonia, en el Sur de Argentina. Esta especie es un paradigma de la extinción masiva actualmente en curso en el planeta: incluso areas remotas, que se podría suponer estuviesen libre de amenazas humanas, están perdiendo su biodiversidad. Las principales amenazas del macá tobiano son las especies invasoras y el cambio climático.

Un grupo de investigadores y conservacionistas pertenecientes a la ONG Aves Argentinas (Birdlife International) está luchando para parar este declive. Hacen un seguimiento constante de todo el ciclo reproductivo de la especie, trabajando en condiciones muy duras, pero recompensados por la observación de los espectaculares despliegues reproductivos. La institución del Parque Nacional Patagonia es uno de sus primeros resultados. Sin embargo sus esfuerzos podrían verse frustrados por la construcción de una represa el el Rio Santa Cruz, que dañaría de manera irreparable la principal area de invernada de los macaes.